“And lets face it. They don’t matter.” - Manual Scavenging in India

privilege (n)

/ˈprɪvɪlɪdʒ/

"a special right, advantage, or immunity granted or available only to a particular person or group."

YouTube recommendations work in funny ways. Their algorithm presents videos based upon your viewing preferences which you are bound to pick, but then occasionally for some trivial reason you happen to not click on it. In most cases, that is that and the piece gets lost amidst a sea of other content. In a few cases however, YouTube persists. The thumbnail then turns up so often on your recommendations and even in your feed that ignoring it becomes a force of habit, without you knowing why. I am supremely grateful that three and half years after the release of “What I Learnt From Climbing Into Human Waste”, a documentary in the Chase series under the banner of ScoopWhoop Unscripted, I finally felt like clicking on the thumbnail. The following 36 minutes, in spite of not being completely uncharted territories for my privileged and entitled soul, were eye-opening enough to write this long an article on it.

The article which follows cannot be claimed to be a completely original one. It is greatly inspired by other pieces of investigative and journalistic content on the internet. It was in July 2012 that Aamir Khan had invited a soft spoken smiling Malayali gentleman by the name of Bezwada Wilson to his well-meaning TV series Satyamev Jayate on a private Indian television network, and the existence of manual scavenging without any sugar-coating had become a reality to me. In 2013, the Supreme Court passed the “Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act, 2013”, and the topic once again received some media glare. My awareness on this social issue has been borderline decent ever since. I’m sure this is exactly what Samdish had thought to himself before he actually took his first step into the backwaters of 2000 mn liters of sewage per day, generated by the 20 million people of Mumbai along with GDP worth $368 bn for the country.

"Now Raju will teach me how to clean what he calls "desi ghee parathas".

Samdish Bhatia, the host of the documentary film, is in many ways very similar to me. He is 27 years old, born to a middle class family in a metropolitan city which could afford quality education for him. While his profession today might be different from the one I will probably end up with in a few years from now, I suppose both of us grew through our early twenties with a certain sense of liberal “woke”-ness about social issues, only to eventually realise that the edification we felt we have achieved is haplessly pitiful. On the whole, neither Samdish nor I am the kind of person you would expect to climb into a city’s excreta. But the fact remains that watching national television from your drawing room offers only a superficial understanding of an issue that claimed 110 lives in India in 2019, which might be what prompted Samdish to walk into an open sewer drain in Chembur, Mumbai. That, and also as Samdish himself admits, “it makes for good TV”.

The work that 54-year-old Raju, an experienced sanitation worker in the Chembur drains, does is not skilled labour. Even after two decades of cleaning human sewage, he cannot claim to have achieved any physical expertise in the field, because the work is as rudimentary as separating a mess of polythene, broken glass, wood and an unbelievable assortment of reject material from the flow of dense thick sewer water and allowing the sludgy pitch black liquid to pass uninterrupted to its destination. The only “instrument” being used is a simple iron rake, which most of you must have seen and a few even used perhaps while tending to your gardens in case you have one. No points for guessing what Raju’s “desi ghee parathas” are.

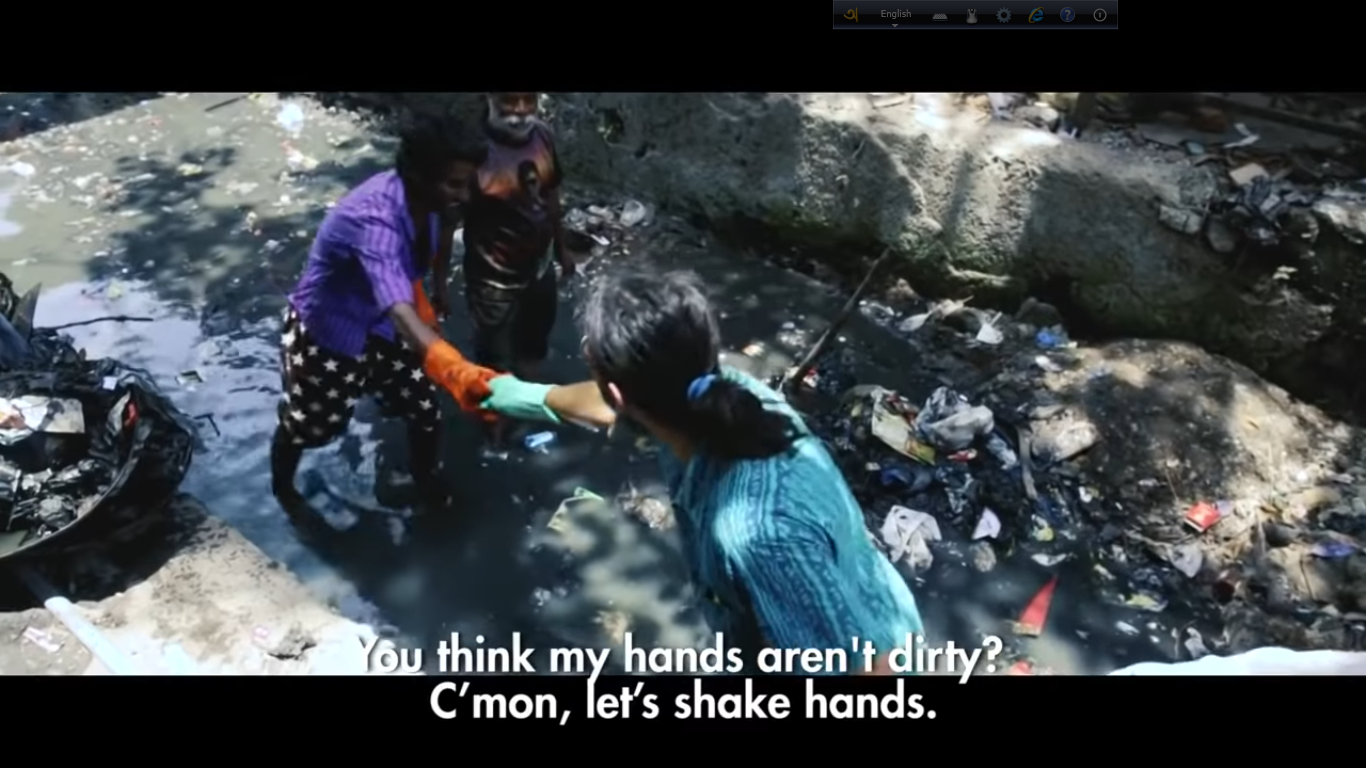

"But with his attitude and tattoos, Sumit, who is roughly my age, seems like a complete misfit in this naala"

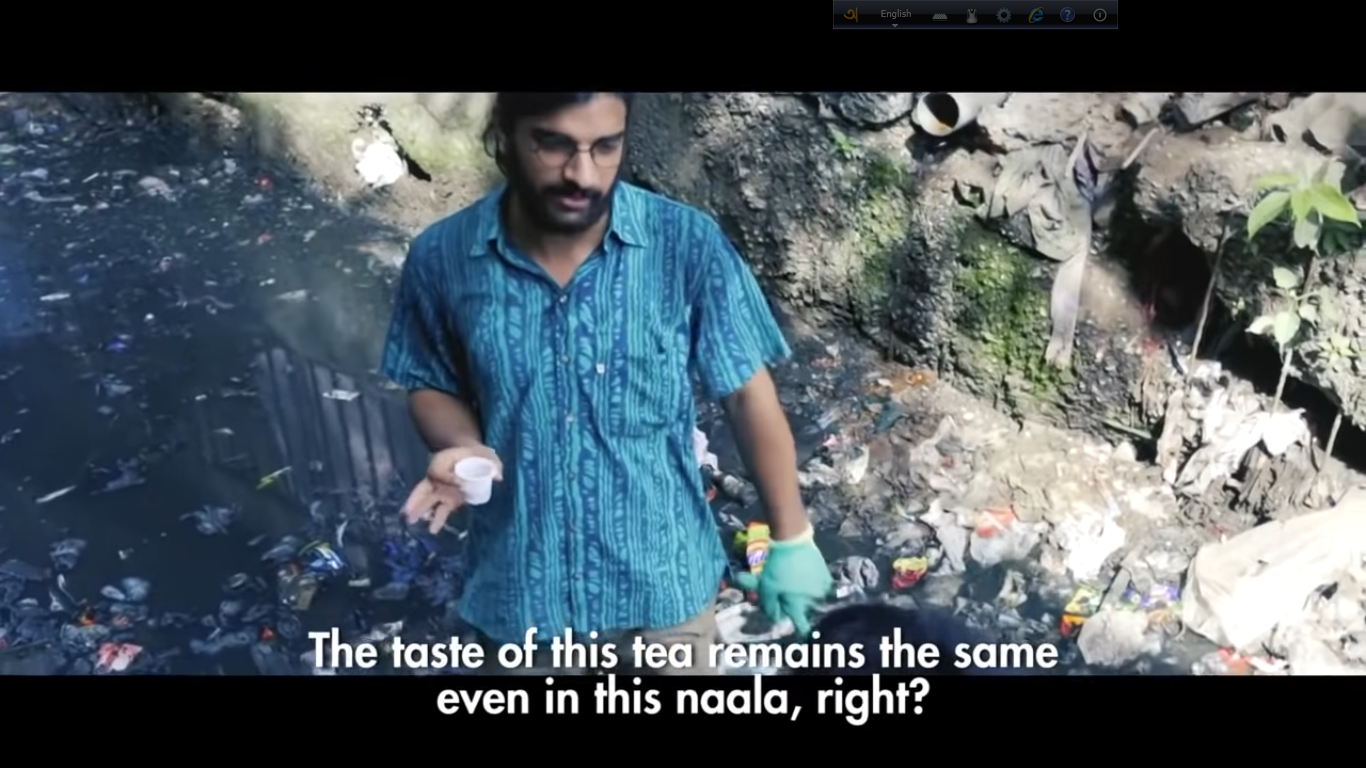

As Samdish’s gumboots fill to the brim with sewer water, other naala characters enjoying this little diversion from their ordinary shenanigans come to the fore. Over a cup of tea held in his ungloved hand, which Samdish says tastes the same both outside the drain and within, the story of these young 5th standard dropouts emerge. Through their rough smiles and amused expressions, it is not difficult to comprehend that they hate their jobs with passion and their regular lives outside the drains are forever tarnished by the very fact of their profession. The harshness of the reality that they do not see any route to escape this literal cesspool of human excreta is as strong as the stench in the drains which is sufficient to make any “ordinary” person puke.

From the sheer weight of negativity and indifferent dejection in the eyes of the workers, surprises do not cease to emerge. Raju breaks into a monologue on how important his work is for maintaining the health and sanity of the city he serves, from Bandra to Chembur, from the heights of Antilla to the slums of Dharavi. Had the more educated masses understood what comes so naturally to this unschooled safai karamchari, there is a possibility that such documentaries need not have been made.

"And second, in the financial capital of the fastest growing economy, why were humans still doing this work?"

By this stage of the documentary, the viewer is past the initial shock and revulsion of an unfamiliar horrifying world, and has probably started asking questions like the one mentioned here. And believe me when I say, this is where the “shit” actually gets real. The bottomline is not too complicated to understand. In the words of Mr. Wilson, at any cost and in any situation, a human being should never be made to enter a sewer drain. The Supreme Court had agreed with this sentiment in a 2014 judgement which had built upon two Acts (1993 and 2013) and directed complete mechanisation of manual scavenging work, recognition of workers currently employed in this practice, and rehabilitation programmes for the same. Here we have at least one example of blatant flouting of this requirement caught and documented on camera, which was being carried out at the behest of none other than the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation, the richest civic body in the country.

BMC is not alone in deserving a lot of scrutiny. The Supreme Court’s judgement reeks of lack of intention and willpower to rid this menace once and for all from India. The 2014 judgement is in itself filled with loopholes. While at one point the judgement dictates all manual scavenging work to be illegal, immediately afterwards a list of precautions is mentioned, which are to be followed in case of an “emergency”. In a system where beyond the law is the norm, this glaring contradiction and apparent lack of willpower is ironic, almost laughable.

"There are so many other poor people in our country but all of them don't do this for a living. There are many illiterate people in India but they don't do this work."

And this is where the mess finally achieves what it has been threatening to do - it crosses over the boundaries of the sewers and enters the ordinary middle class households in the form of a monster that has affected the lives of not only men and women in this profession, but the sheer existence of generations of exploited, abused and helpless humans. I wonder how many people on LinkedIn are comfortable in venturing out of insulated corporate existence to discuss caste.

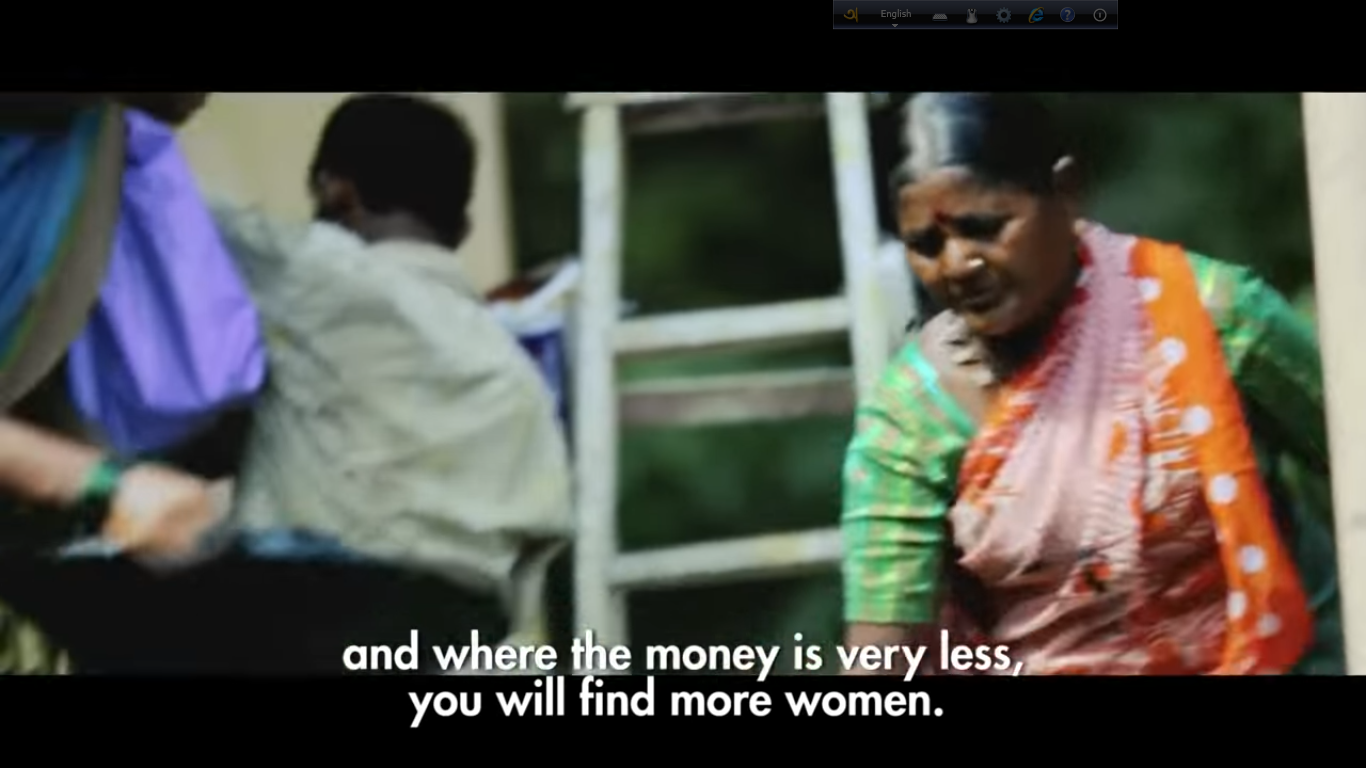

Education adds value to an individual, and in return the individual starts valuing the education. Weirdly enough, this has its set of consequences. Acknowledging the utility of education in breaking social barriers is a no-brainer, but people’s vision run the risk of turning myopic towards those issues which education does not necessarily eradicate. No, grossly improper though it may sound, ensuring education for all does not solve every social problem. Nothing exemplifies this unapparent reality more than the manual scavengers of India. Caste in India is rooted in the four varnas followed by a fifth layer which not even a part of the system - the Dalits. Professions being selected on the basis of caste was a reality in India until two centuries back. The hegemony (and enforcement) of certain castes over certain professions has been been moderately scratched but not nearly eradicated, since complete homogenisation of professions is still a distant dream. But thriving vestiges of occupational ostracising still live within the gutters of India, pushing a profession into systematic discrimination which is generations old. The numbers of poor and uneducated in India is booming, but beating the law of averages which would have meant proportional distribution of all castes in this hapless profession, every single manual scavenger in India is a Dalit.

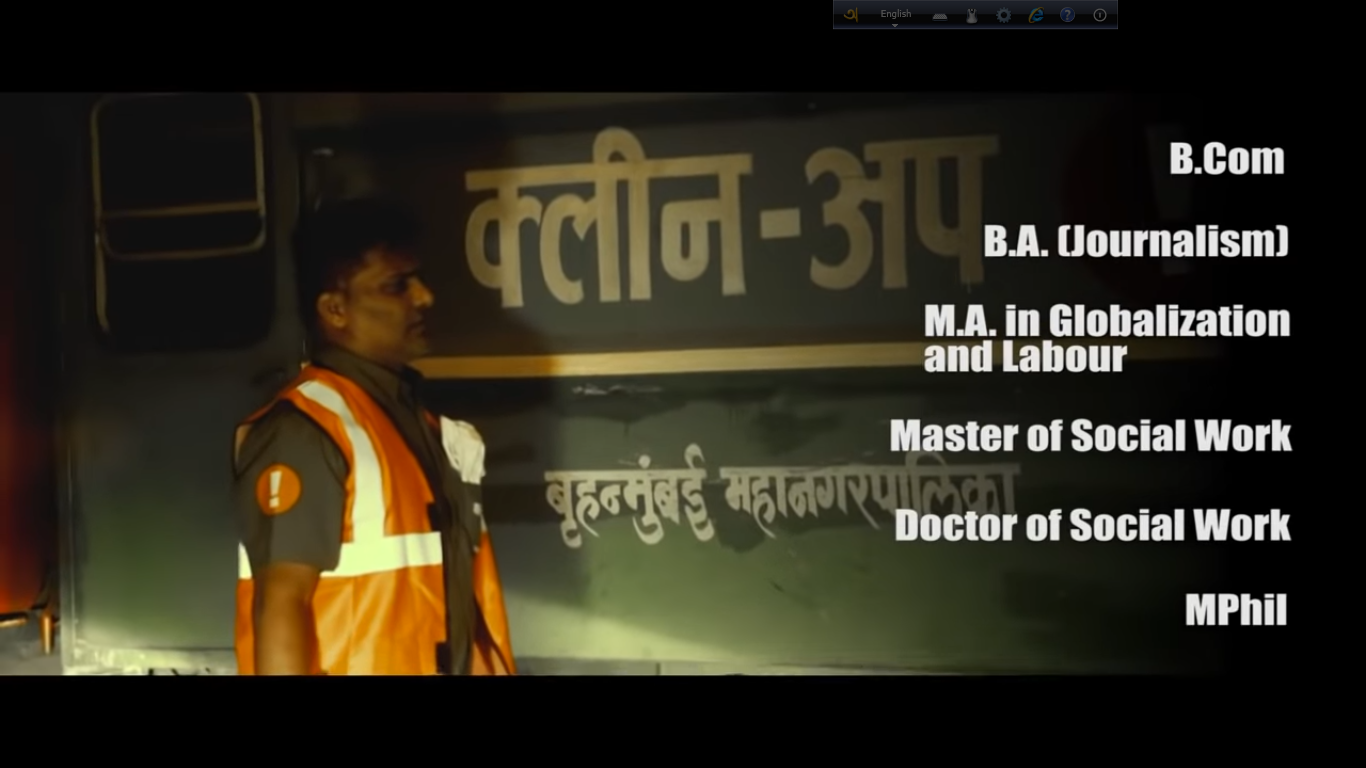

Sunil Yadav

BCom, BA (Journalism), MA (Globalization and Labour), MSW, MPhil, DSW

PhD student, TISS Mumbai

Safai karamchari, BMC

It is not possible to conjure up this surreal combination of elements into one person in fiction, but the very existence of Sunil Yadav goes to demonstrate how fiction doesn’t hold a candle to reality. If you are a fourth generation safai karamchari, chances are you do not even get a decent shot at educating yourself. Even if one works his way up to higher education, such a person going ahead to receive six degrees and working towards a seventh one is stuff dreams are made up of. Reality serves you the complete assortment of emotions when you realise that Sunil is still night-shifting the profession of his forefathers while attending academic seminars in the day, and even such staggering volumes of academic achievement is not sufficient to pull him out of a profession that should not even exist.

Education empowers people with grit, resilience and sheer force of will. Sunil has broken a chain of alcoholic and abusive ancestors to make sure his children get a better future. Even Raju, with no formal education, has made sure that his children have studied till 12th grade and support their resolve to not take up their father’s profession. Education has the capacity to pull through individuals from this quicksand, but not the whole society. While Raju and Sumit might have succeeded, there would be thousands of other workers descending inside hell-on-earth septic tanks and manholes who will succumb to the weight of generations of exploitation. Education alone cannot pull them up, both literally and figuratively; lawmakers and administration need to step in.

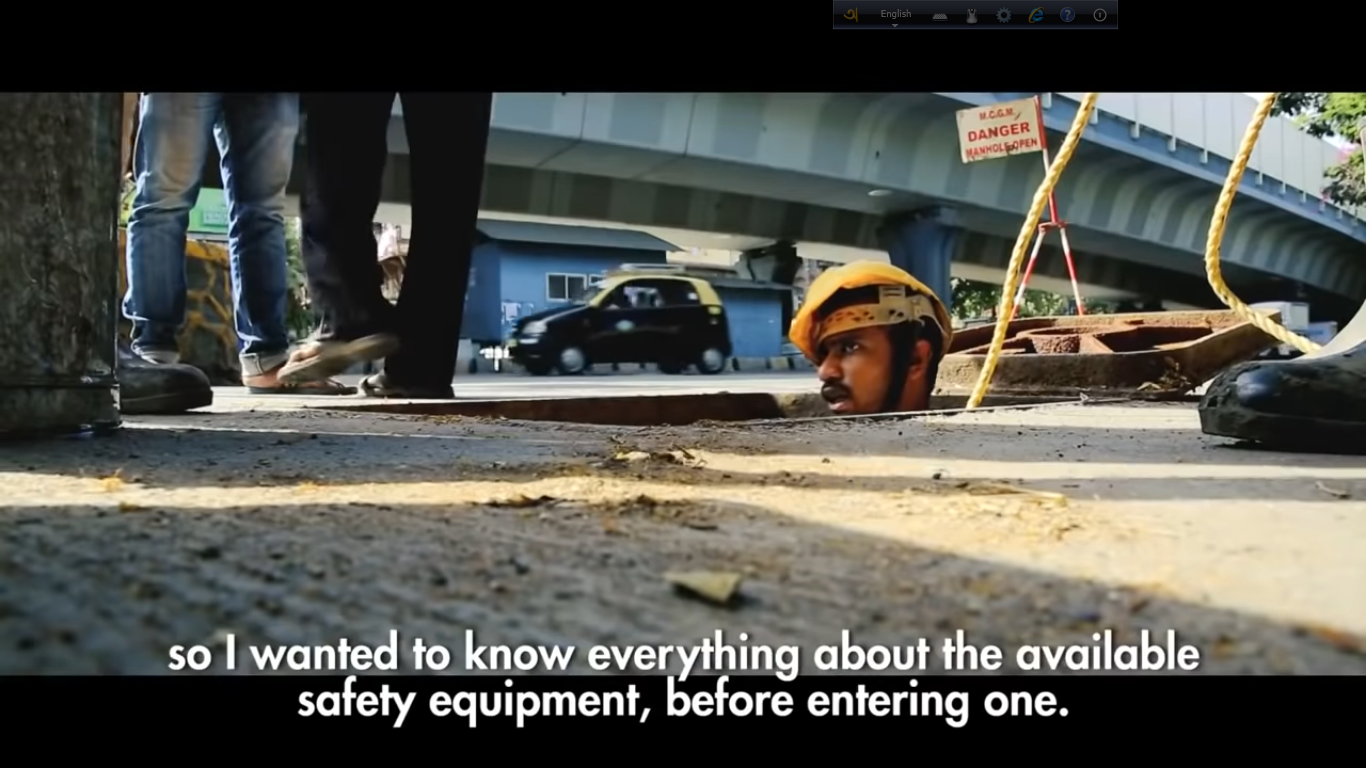

"When I brought up the topic of going inside a manhole, even Raju, who was opposed to the idea of wearing gumboots, basic safety precaution, expressed his apprehensions flat out."

The horrors for the viewers continue. I remember an open vat on a by-lane on my way to senior school which I would occasionally have to pass by. The stench was disgusting. I had assumed the vapours in Chembur’s open drains were a thousand times more nauseating than that open vat. But now we were not talking about sickening smells, or vile surroundings, or spreading of diseases anymore. Manholes and storm drains can mean instant death for a manual scavenger.

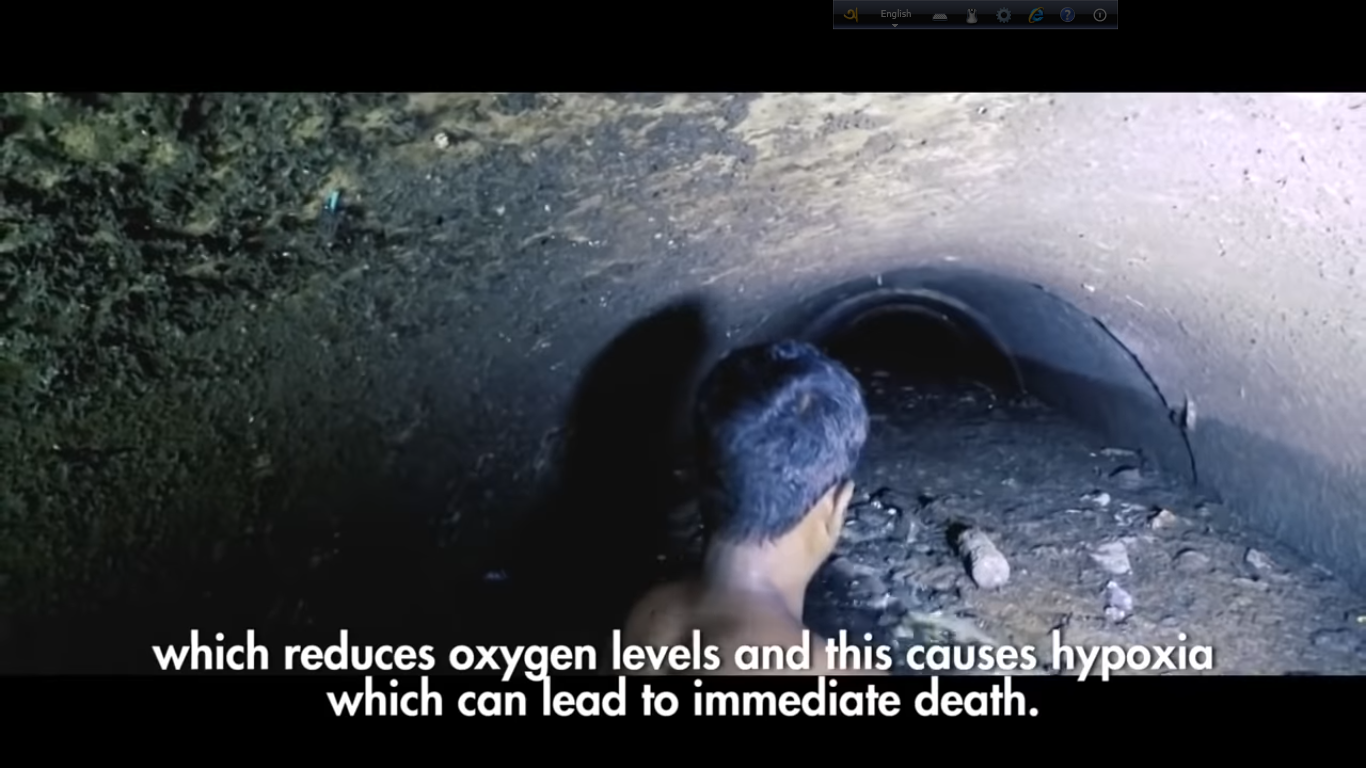

The combination of wastes residing in a manhole is metaphorically a chemical landmine. Decomposition of the various components of biological and non-biological waste can result in emission of noxious and poisonous gases which displace oxygen from the air - the life source for humans. A “candle test” is performed - an utterly rudimentary form of a procedure to determine the quantum of oxygen inside the drain - and then the scavenger descends inside to service the installation. Samdish notes the safety equipment brought to the site; it is only figured out later that the equipment are for the benefit of inspection personnel or one-time visitors like the ScoopWhoop Unscripted team. It is not difficult to figure out that fatalities are not the rarest of incidents.

"There were two more workers with my father that day. All three of them passed away."

While Samdish quotes a different (much higher) figure, The Hindu reports that manual scavenging deaths in India jumped by 62% to 110 in 2019. According to The Print, the number of manual scavengers has definitely come down from nearly 8 lakh in 2003 to around 13,000 in 2013, but the number shot up threefold by 2018 and you are left to figure out why. The attention and focus being directed towards bringing the entire population within the sanitation system is undoubtedly a justified initiative, but is it not equally necessary to equip the civic machinery to deal with all this human waste without having to fall back upon a medieval and inhuman practice? Even a single death to this curse is not acceptable in a civilised society.

In categorising these deaths as “accidental”, a huge disfavour is being done towards the community. Accidents occur due to unforeseen circumstances or uncontrollable errors in a process which is otherwise safe and manageable. When the occupation itself has been repeatedly been declared unfit and unsuitable, the problem is swept under the carpet disguised as “accidents”. Without resorting to exaggeration, it is safe to say the workers are running the risk of their lives every moment they are inside the muck. The kin of the deceased then find themselves running pillar to post to receive the compensation they are entitled for.

"He has taken a dip inside."

Even the documentary crew had not been prepared for what they were unearthing. A change in plan was necessitated, and Samdish was not to descend down a manhole for being too risky. Instead, a storm drain awaited him. And within the storm drain awaited half-submerged Sourav, who from his accent was clearly a Bengali like me, cleaning the sewers of a city far away from his home. When Samdish asks how he survives without falling sick, Sourav replies with a distant look, “Bhagwaan ki mitti se bana hua hu”.

While the canals of Chembur had afforded the luxury of at least having an open sky above, a storm drain, which carries drainage water to the ocean, is not very easily believable even upon viewing. A full body-suit with state-of-the-art PPE’s along the lines of what sewer workers in other civilised nations use could not have made Samdish venture further down the circular gateways to hell. Meanwhile Sourav returned floating with a thick solid cake of refuses of the size of two dining tables.

"...if we are mentally alert while working, then we won't be able to do this work."

“Punish the crime but not the criminal”. Crime of any sort is indefensible but is it sufficient to just take the criminal to task? An overwhelming majority of the sewage workers are alcoholics and drug addicts. While these menaces were admitted without hesitation on camera, there are probably other associated (undisclosed) vices which have them in their grip. These vices are destroying the entire community, their families, often spilling over to those outside the community. Do you really blame them for the substances they have resigned their bodies to? I have read tales of fighter aircraft pilots who could not walk a step on firm ground without first having a puff of nicotine upon returning from an aerial dogfight. Ordinary humans have limits till which they can stretch their capacity for stress and trauma. The manual scavengers are mandated to do this every day at work. Numbness is the only escape that allows them to descend into hell.

These workers are all acutely aware of how they are trading their lives for this livelihood. Since the profession is handed on through families, they have all seen their forefathers succumb to early death under duress from inhuman working conditions compounded by alcohol and substance abuse. I could not make out if Raju was putting on his theatrical best when he told the camera that death is their only escape from this life; either way, maybe he was not far from the truth.

"Everyone just seems to be passing the buck here; no one's taking the responsibility."

Ah, familiar waters. Incompetence of authority - something we all can identify with, which is a pleasant change from death of sewer workers due to asphyxiation and methane poisoning. The team at ScoopWhoop Unscripted spent two weeks trying to get in touch with the relevant authority at the BMC who would be in a position to clarify the corporation’s position on the situation. The intention was clear - since the raw footage shot for the documentary does not show the BMC in the brightest of lights (and Maharashtra is only fifth on the list of sanitation worker deaths, so they are surely not the only culpable civic body around), it is only fair to let them put forth their viewpoint upon the table. After two weeks of shuttling to and fro across departments, divisions, engineers and their PA’s, the permission for an on-camera interview could not be attained - even the competent decision-making authority could not be identified.

The problem is not BMC’s alone to solve. Honestly, not a lot of people give a thought to the contents of our bathroom and kitchen wastes once they leave our houses. The problem is multi-dimensional. The society is having to deal with issues of dry latrines, absence of toilets within homes, wastewater treatment and an assortment of issues, all at the same time. The humanitarian aspect in manual scavenging is one particularly evil manifestation. In a thriving democracy the best way to get things done is to raise public awareness on it, so here is a humble attempt at doing my part.

"And lets face it. They don't matter."

The worst of sufferings are undergone by those who cannot speak up for themselves. In an unenviable stranglehold of caste, poverty and social apathy, these manual scavengers are dying every week, within our own cities, but they are mostly not even registered into public memory. Among those who will have reached the conclusion of this article, I am considerably confident that we are all a part of the definition of “Indian privilege”. We can afford to not know about Raju, Sunil and Sourav, because we have the prerogative to not get affected by their lives, or deaths. But each of us has the ability to contribute meaningfully to the fight against a social malaise so deep rooted. It is a simple matter of asking questions, raising awareness, and making sure you know where your shit is going.